The stimulus card is arguably one of the most demanding tasks in AQA A-level languages. You may be familiar with some of the issues that students commonly encounter when dealing with the card:

- Ineffective summarising of the text

- Basic, superficial opinions & difficulty providing justification

- Lack of ideas / repetition / drawing blanks

- Banal, basic, repetitive language

- Lack of fluency

I believe a lot of the above issues can be tackled through effective long-term planning, targeted lesson activities that break down exam technique and plenty of guidance for students on how to approach independent practice and revision.

All students tend to find this exercise very challenging initially, but they can do very well with the right preparation and attitude – I have taught and/or tutored students who have gone from B/C standard in their mock to A*/high A in this task. By sharing some of the strategies we found most effective, I hope this post will be useful for trainees, recently qualified teachers, or perhaps more experienced teachers who are teaching this specification for the first time.

This post is Part 1 of 2, and here we will focus on the role of long-term planning and selection of teaching materials. Here are 5 ways you can ensure the demands of the card task are accounted for in your planning and resourcing of the curriculum:

#1 Build in regular practice right from the start of Year 12

It takes students a lot of practice to get familiar and confident with this task, and there are a lot of different elements and micro-skills they need to master. You can therefore:

- Incorporate plenty of practice cards into lesson time – more to come on this

- Include the card task in internal assessments throughout the year

- Have students practise cards with a language assistant if you’re fortunate enough to have one

- Allocate practice cards for homework, either as writing or speaking (both are beneficial) to practise technique and content. Students can prepare their notes for homework and then the speaking can be done in class, or they can submit voice recordings of them reading prepared paragraphs – whilst we don’t want to encourage reading of notes generally, reading aloud practice is still beneficial for acquisition of content compared to writing alone.

#2 Keep Question 3 in mind when defining objectives for each unit, selecting resources and planning lesson activities

Question 3 of the card tends to be the big opportunity for showing cultural knowledge. Given the weight of the other skills (Paper 1) in the A-level, it’s easy to overlook the speaking component or see it as a task to practise in separate, isolated lessons, but so much of your lesson content across the course can be utilised to help students build their bank of cultural knowledge for question 3, in particular.

They need to have a range of ideas and examples at the end of each topic, so it’s a good idea to look at past speaking cards on each topic before you plan your lessons, rather than just the textbook, so you can be guided in how to exploit the content. The ‘indicative content’ in the mark schemes can be very helpful.

#3 Before doing lots of research for examples and facts, exploit all resources you already have

Sometimes, students and teachers think they need to research loads of statistics and news items to find material to discuss during the card task. This may be true for certain questions, but many of the teaching materials we already use are rich sources of relevant facts, trends and case studies, such as:

- Texts from the OUP/Hodder textbooks

- Listening transcripts from the textbook

- Reading/listening worksheets from Kerboodle

- Past paper readings and listenings

- Past speaking cards

Students often don’t realise that these texts model exactly the kind of content that they can talk about in their speaking – make them aware of this early on in the course as it is motivational! We often use texts and listening transcripts to practise exam-style comprehension or vocabulary-building, but we should also be using them to build students’ knowledge portfolio for the card.

For example, we can: - Write comprehension questions or tables that are targeted towards eliciting key issues – these will also help students produce revision notes more efficiently

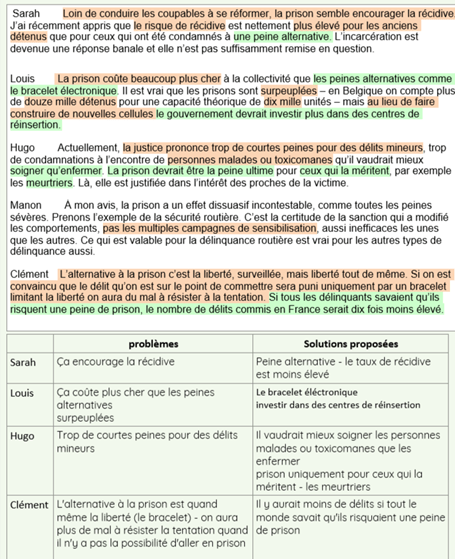

- Use colour-coded highlighting/underlining to identify key ideas, arguments and evidence (see examples below) – you can provide headings in advance for pupils to match if you want a quick, focused activity

- Use the text as a springboard for practising the opinion/reaction question – this can be practised in response to almost any text encountered in class

You can also find some very good ready-made fact-files. These ones by LaProfdeFrançais are extremely detailed (probably a lot more so than necessary) and these ones from French Top 10 have some pertinent examples. I’ve also seen some mind-maps made by students available on TES, although they may need checking for language errors!

#4 Fill gaps in content using AI to take shortcuts

It can be frustrating that some of the Question 3s seem to require topic knowledge that isn’t really covered in the textbooks, and even if it is, time does not allow for students to extract and discuss every idea and example from every text. For this reason, I often use AI to help me – here are two ways you can use ChatGPT:

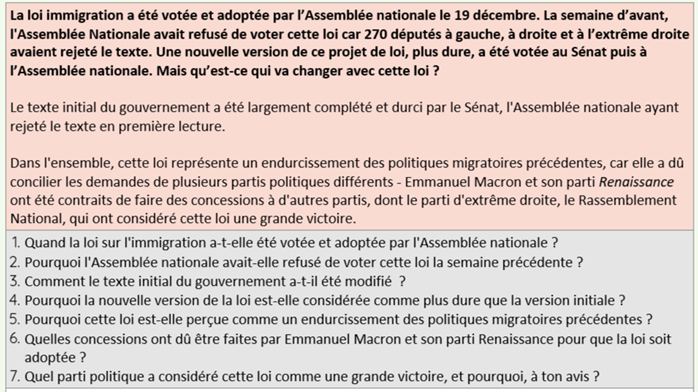

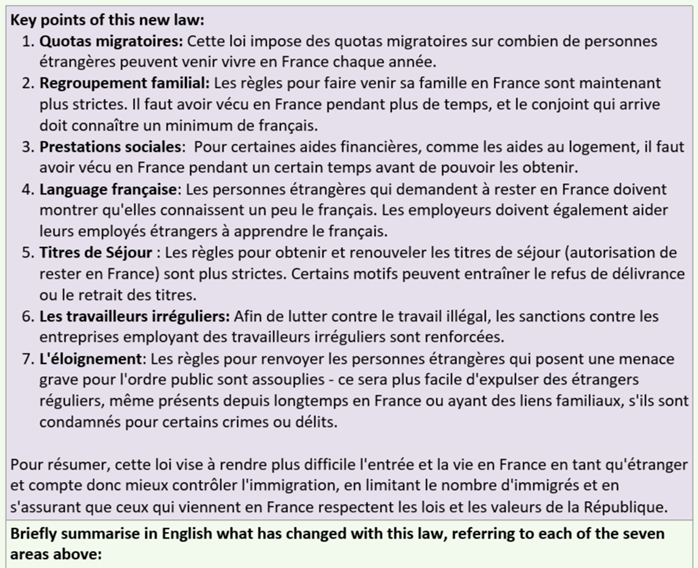

- Summarising news items: If there is a recent news item that is really useful for your students to know about, but articles on it are very long and dense, you can paste the article into ChatGPT and ask it to create a summary, then make some exercises on it. See the example below – in January, I wanted to teach students about the new immigration law in France and ended up with the following texts and activities:

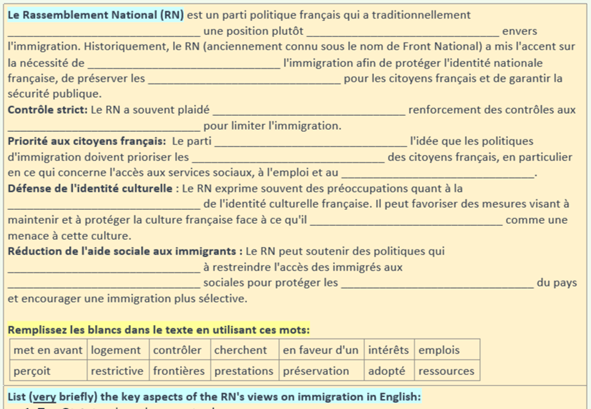

2. Explaining general trends, arguments or ideas: you can also ask ChatGPT to summarise content eg. arguments for and against something, main views of different groups – here, I asked it to summarise the Rassemblement National’s views on immigration, which I then turned into a gap-fill as a basis for discussion.

Sure, the above texts do not necessarily display the same density, idiom and grammatical complexity you would see on an A-level exam reading comprehension, but that is not the purpose here – we are modelling language for pupils to use and giving them clear, comprehensible input so that they can acquire it and use it effectively.

#5 Build in regular retrieval opportunities for Question 3 content

You can set homework to memorise their notes on a particular sub-topic and do a linked retrieval starter eg.

– brain dump of everything they remember on the topic

– writing a draft paragraph answering a past Question 3 on MWB

– writing lists of points or examples under different headings/prompts given by the teacher

– writing a series of quickfire answers to randomised questions from a list inputted into wheelofnames.com

– writing a list of every point they would mention if they had a card on a particular topic. Eg. if they get a card on marriage, they can talk about causes of the decline in marriage, causes for increased divorce rates, changes in gender roles, the alternatives to marriage, other changes in family structure such as single-parent and same-sex parent families etc.

So, let’s return to our initial problem, the 5 issues commonly encountered on the speaking card:

- Ineffective summarising of the text (A)

- Basic, superficial opinions & difficulty providing justification (B)

- Lack of ideas / repetition / drawing blanks (C)

- Banal, basic, repetitive language (D)

- Lack of fluency (E)

Effective curriculum planning and resource selection mean we can tackle problem C – lack of ideas. When students have ideas, they are also going to find it easier to form opinions (B). Having exploited the content from teaching resources effectively, they are also more likely to produce these ideas in high quality language (D), and if they get enough practice and revision of these ideas, they can also improve their fluency (E).

Part 2 of this blog is coming soon, where we will explore targeted lesson activities that break down the elements of exam technique, as well as how to guide students on revision.